Dolls can operate as hosts if the work can hold energy. I am working to create such energy in my artwork….The work is my method of decolonization of self.

––Cheryl D. Edwards, Artist Statement (2022)

In 2020, as the rest of the world was in lockdown, Cheryl D. Edwards had to close her studio. I watched as she brought home her paintings, blank canvases, boxes of materials. We have been neighbors for more than a decade and it felt strange that I could not help her unload the car but, even masked, that felt unsafe. There was so much we did not know about Covid-19. We were all lonely for our communities but I knew this was especially painful for her because her studio, part of a revitalized artist row called Brookland Art Walk, had also been where she met with other creatives from artists to writers and gallerists. I called her and we sat in our respective living rooms, a few doors apart trying to make sense of the world. As the pandemic deepened our relationship as neighbors, it also expanded our conversation about politics and public health, liberation and creativity. As the weather warmed, Cheryl brought her easel to the porch and began to paint again, making sense of the world in the best way she knows how—through her art. One day in the summer of 2021 Cheryl warned me that she would be scarce for a week. She didn’t want me to worry if I didn’t see her car or she didn’t answer the phone. She sounded excited. She was going to work at a friend’s studio, to have an opportunity to learn a new medium—hand papermaking. This is a profile of my dear neighbor and mentor Cheryl D. Edwards. It is based on years of casual conversations and a series of interviews that took place between March 2020 and January 2023.

Olivia Love Edwards, a pharmacist, and Clarence Leonard Edwards, a porter at Eastern Seaboard Trains, built a middle-class life for the family in Miami Beach, Florida. Though her parents paid for piano and dance lessons, Cheryl recalls, “They wanted me to be a doctor or lawyer or teacher or things of that nature. Money. Money. Artists don’t always know if they are going to be able to support themselves with their art. So being African American in America, what was important to my family is that I would be able to make a life and support it.”

There is a picture of Cheryl as a child, unsmiling and staring. From the picture, you would guess she was not a child who played with dolls. Even at that age she understood that dolls intended to domesticate her. “In America, we are given dolls to change the diaper, to feed the baby,” Cheryl says. “It is a role-playing tool for young children to practice motherhood. To practice wifehood.”

Cheryl wanted to be an artist but she went to law school, passed the bar, and moved to New York City. By day she was an administrative law judge and by night she was an art student. She began to travel, first to West Africa and then, when Nelson Mandela was freed, to South Africa. Later, she went to Egypt to see the pyramids. She longed for a child and became a mother, but was never a wife. All the while, she was an artist who would paint late into the night after her son went to bed. Looking back on it now, Cheryl says, “It was all a pathway to visual arts.”

It was while in Africa that Cheryl found her subject: dolls. “Ndebele children play with dolls,” Cheryl says, going on to explain that for men “to bury a doll is part of courtship. And the women use dolls for healing and fertility and marriage celebration. We didn’t have those kinds of usages in the West.”

Inspired by the Ndebele community, Edwards began her first series of representational paintings in oil. As she branched into watercolor to woodcuts and ink, the dolls became more abstract in form and complicated by her research about their usage. Then she began to paint the paddle dolls originally associated with ancient Egypt. The exact purpose of the dolls is unknown. Early male-dominated scholarship insisted that they were sexualized symbols and concubines for the dead. However, as more women historians have come into the field, these assumptions have been challenged. The dolls are often found alongside women and children, suggesting play and ritual meanings.

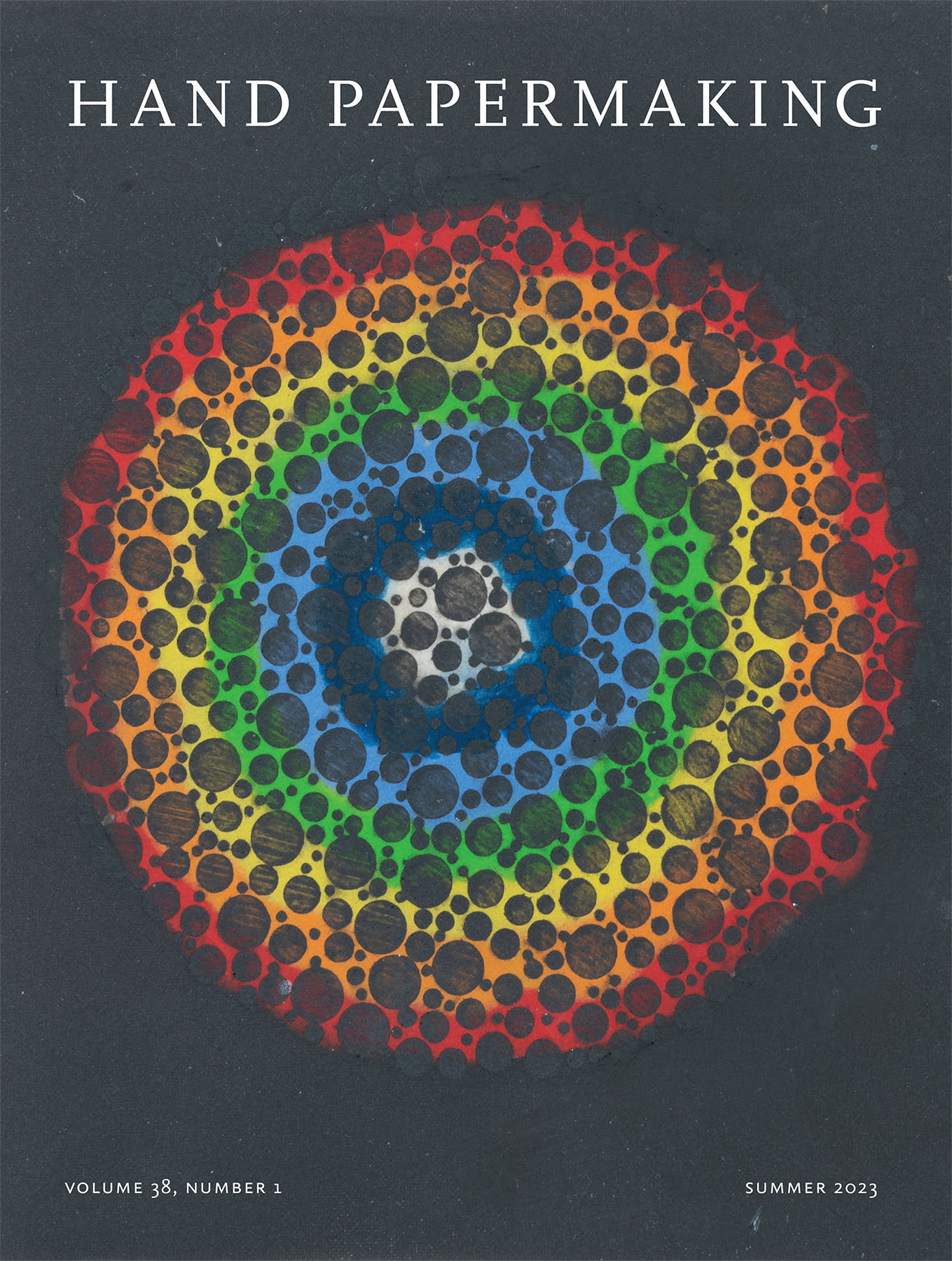

Named for their shape, paddle dolls are only vaguely human-shaped with intricate hair and carved patterns all in the neutral colors associated with the materials. By contrast, Edwards’ dolls are all rich with color, as if returning to the palette of her childhood, where she grew up with “Black folks and Cubans—largely. And many of the Black people in Miami descended from the Bahamas. So there was always this cultural Caribbean environment. And you know how people wore colors. For people of color, our cultural statements incorporate color in a loud manner.”

For Edwards, these dolls are a way of returning to precolonial imagery and the mysterious powers of women. She calls her paddle dolls, Water Angels, as they were born of a period in her work when she was reminded of the sacredness of water in many spiritual traditions.

For years Helen Frederick had hoped to interest Edwards in making paper and pulp paintings. Edwards admits, “Helen [Frederick] has been inviting me for years [to her studio]. I have seen her work, and other pulp painters too, the result not the process. But I had tried not to deal with it. It was not my thing. Same with printmaking at first.”

Like everything else changed by Covid-19, Edwards’ attitude and interest in pulp painting were changed too. In the midst of the pandemic, she felt “the urgency coming with not knowing if we would be alive or dead. And I had shut down my own studio. It was such a pleasure to go somewhere else. To learn something else. To learn something brand new.”

Using pulp painting as medium, stencils, and even woodcuts, Edwards brought her paddle dolls to paper pulp. It was exhausting work, from the oversize substrate to hauling the five-pound buckets of pulp, to the flipping, rollers, and pressing. The process was more labor-intensive than oil painting. For Edwards, “the physicality [of] pulp painting [is like] that of printmaking. It is a democratic process and requires a village to put it together.”

Edwards likens the process to watercolor. “You just have to work it. What you are looking at, everything is wet. The color it looks like in that moment when it is wet, isn’t what it looks like when it is dry. You are not sure how integrated the composition will be when it is dry. So you don’t have so much control. There is more of a surprise. In some instances the surprises are very good. And very beautiful. An unpredictable outcome.”

It was also faster. While she can work on oil paintings for weeks, even months, with pulp painting Edwards made ten paintings in two days, all the while working against time. In the midst of the process, she was struck by the sculptural and three-dimensional aspects of the work. As her pieces dried, she was able to see the more painterly aspects of the brushstrokes and integration of the colors. After working with paper pulp, Edwards realizes that she returns to oil painting with a deepened understanding of layering. As someone new to the field of pulp painting, she recognizes and thanks more established pulp painters for building a welcoming community.

Cheryl returned home from the weeklong papermaking session exhausted but she texted me pictures of her time in the studio. Usually I see Cheryl’s work in process, but this time I had to wait. When she brought the dried pulp paintings home, Cheryl called me over to come see them. Each one already complete, the texture of the pulp paintings was like a relief map of a mountain range. Cheryl allowed me to run my finger over them but I could not focus on each one with so much new work at once, until she lifted a bright pink piece. I stopped her, What is that?

I Live in Two Worlds, she told me. Usually, her paddle dolls are centered and fill most of the composition. But in this one, the doll is only about half the canvas, and off to one side. The space around the doll brings in the idea that it is part of a wider world to be viewed. The background includes a woodcut that Edwards has used before, but will not use again after this piece. The woodcut block was inked with fuchsia pink and printed on top of the pulp painting. The doll seems to rise out of the shadows. It was not an accident, but an intentional artistic expression driven by the lockdown and Covid-19. “I reference the Great Wave off Kanagawa woodcut by Hokusai Katsushika and a contemporary water angel using the Egyptian paddle dolls as a metaphor,” explains Edwards. “I am attempting to make a statement about the oneness of humanity and the pandemic that equalized us, although we were not all in the same boat.”

author recommendations

For more about Cheryl D. Edwardsʼ art, go to these online resources:

• Website: https://www.cheryledwards.org/

• Instagram: cdedwardsstudio

• Lecture: “African Dolls: A Scholarly Talk,” sponsored by George Mason as part of the exhibition “Cast/Recast,” with Cheryl D. Edwards and Ellen Morris, Associate Professor of Ancient Studies, Barnard College, Columbia University, https://www.masonexhibitions.org/exhibitions/castrecast.

Pulp paintings by Cheryl D. Edwards will be featured in the exhibition “Eternal Paper” at the University of Maryland Global Campus, Adelphi, Maryland, October 15, 2023—January 5, 2024.