Mary Hark—artist, papermaker, teacher extraordinaire—works with color in surprising ways. As Professor of Design Studies: Textile Design and Papermaking, University of Wisconsin–Madison, she attributes her unique palette and working process to her early training in textile design.

Whether connecting to children in her culturally textured neighborhood where she is the proprietor of HARK! Handmade Paper, or in Ghana, where she makes editions of paper in collaboration with Ghanian artists and local communities, she is constantly advocating for sustainable papermaking, and always experimenting with color.

I met Mary last year, through a program run by the Minnesota Center for Book Arts, to talk to her about her plan to make a set of bound volumes that would bring together different bodies of her paper of many colors. We met again online in November 2022 for this interview on her approach to color. I was in Lakeville, Connecticut. Mary was her studio in St. Paul, Minnesota.

From where I sit, I see multicolor piles of paper on tables, and some unidentifiable rusty red and brown objects on the wall behind you.

Oh, there is such pleasure to be had in the material world. The objects on the wall are metal grates, made to be placed over a small coal fire to hold a pot of water for making tea. I used to find these in the market in Ghana. The surface of each grate reveals its history, with color from the original metal object that the grate was fabricated out of, additional layers of new paint, rust, and scratch marks from incidental handling.

Could you tell me about your house and your studio in St. Paul?

The house was a gift from the Universe. In the 90s, I was the beneficiary of an urban renewal program created by a non-profit called Artspace in St. Paul. At that time, Artspace bought dilapidated houses and restored them for low-income artists. These homes were often in new immigrant communities where artists and their adopted neighborhood could benefit from intercultural exchanges. I’ve been fascinated by this neighborhood for the 26 years I have been here. I’ve had the opportunity to invite neighbors to participate in a community art project and to invite kids who have wandered down the alley to join in with work that was happening in my studio. One of these children was Tony Santoyo who started coming over when he was eight years old. He assisted me on many projects over the years, and eventually obtained a BFA from the University of Minnesota, and now is completing a three-year residency at Penland. He is a wonderful artist—a papermaker, painter, and potter.

In a sequence of images you shared with me, you capture some of the steps in your working process, and also provide a short text: “My papers are made from flax and abaca because these fibers are strong enough to withstand multiple dips in a dye vat. The papers are painted and then overdyed with a walnut patina multiple times, gelatin sized, and then put back in a restraint dryer to flatten them. The walnut dyes are made from walnuts I collect locally. The multiple dips in a light dye causes the colors to separate and run, and also causes any imperfections in the sheet to become exaggerated.” To begin with the first application of color, how do you paint the paper?

To start with, I make paper using flax, abaca, and linen—fibers that produce a paper that can withstand a lot of surface work and can be immersed in a dye bath after it is dry. Then, after the sheets are made and dried, I paint them using raw pigment. I mix color, and then with my big paintbrush I roughly cover the sheets on both sides with saturated color. I generally paint editions of 100 sheets at a time. The painted surfaces are a bit irregular with areas that are heavily painted and areas that have thinner layers of paint. The color I choose can be driven by a commission, or more likely it is color I am inspired to use.

What colors are those?

Lots of reds, oranges, warm browns, different greens, and of course blue. I do use a lot of indigo. I use it aggressively to make it deep and dark. When I use indigo with a heavy hand it becomes almost metallic, and has an earthy, almost dirty quality. These indigo sheets carry uncommon blues, deep and dark. The color I gravitate toward is intense, complex, worked, almost bruised. I love all colors, though I am rarely able to find pastel tones that work for me. And each color edition is unique. I mix each batch of color intuitively.

Some of your papers glow like an Old Master painting. Others shimmer like copper. How does that come about?

After the paper is painted, I pull each sheet through a walnut patina several times. I collect walnuts from the neighborhood. I let the walnuts decompose for a season, which results in a sexy deep brown compost. I boil and strain this material to get to the patina. The painted sheets of paper are then altered with multiple dips in this walnut patina, with the sheets air drying between baths. This process modifies the color, emphasizes inconsistencies and irregularities in the paper surface. In the end, the color becomes inseparable from the tactile surface of paper. These papers have a real history. The labor of making each sheet is part of the story. Every sheet is unique, even within an edition. The labor in this process appeals to me. It is a fundamental value in my practice.

From the moment you select your fibers and begin to create paper you anticipate color as essential, as the main event.

Yes, I think because I come from a textile background, I approach the surface of paper in the same way I first learned to work with cloth. That background in textiles has allowed me to work with a palette and an approach that is not typical in papermaking. Ordinarily a papermaker would pigment the pulp and have that color come from inside. Instead, I paint and alter the surface, I exaggerate imperfections and emphasize the organic nature of the material. The flaws, the less than perfect, the incidental mark, interest me.

When you say you exaggerate the imperfections, what do you mean?

[Laughing] Maybe it’s a reflection of my lack of mastery! All that wetting and drying exaggerates any imperfections that occur when the sheet is formed. And I love that. After the final patina the paper gets a heavy gelatin size. This doesn’t change the color, but it emphasizes topography and adds a subtle waxy surface. It seals the surface so that someone using my paper won’t have to worry about the color rubbing off.

You have made many collages, and many refer to place and landscape. For example, I believe your series of collages called Driftless Reveries were inspired by your long drives to and from Madison and St. Paul.

The Driftless Reveries collages are composed of paper offcuts that carry the color and tactile surfaces that begin with the sheets of dyed, editioned papers. To some degree they reflect the topography, geology, geography, and light I see on my drives to and from Madison, which is always changing with the seasons. There is, for example, a red that appears occasionally at sunset in the Midwest, but it is also a color I know from traveling in other parts of the world. I made the collages in response to the landscape I see on these drives, but they also reflect other of parts of my life—my domestic environment, weathered surfaces that I remember from working in Ghana, the way land is organized in rural Wisconsin, a passage from something I have read, the changing light of late afternoon. You know how your mind wanders while you drive a distance? I am driving through a specific place, and I am ruminating on experience. These pieces reflect that.

When we first began to talk about books last year, you described your plan to make a group of swatch books that would gather together five bodies of work on paper you’ve made. Can you talk about that set of volumes?

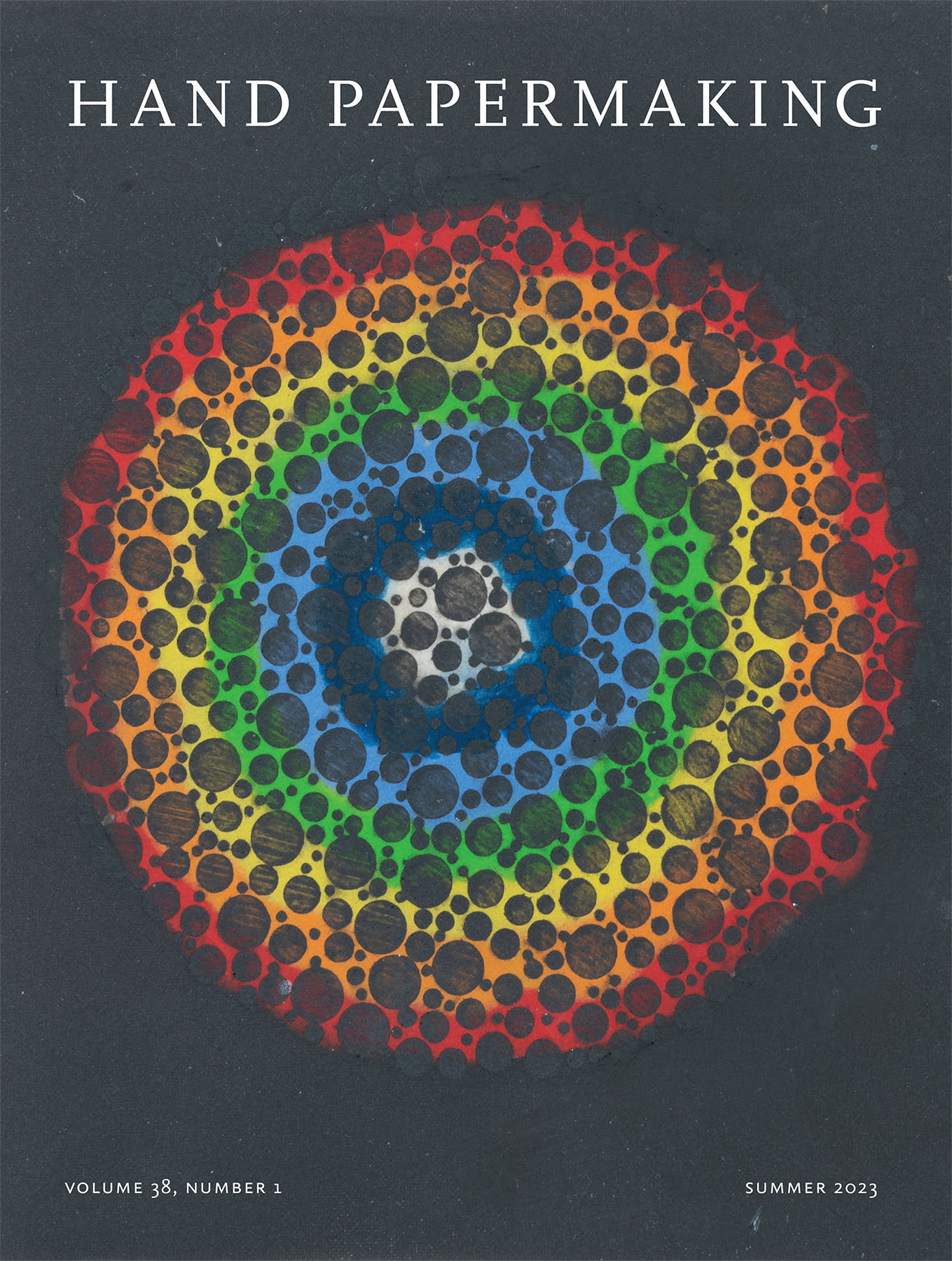

Yes, I am working to create a small library of limited-edition fine press artist books titled together, Material Evidence. This series will eventually consist of five distinct books. Each of these books will be housed in a paper-covered clamshell box and include a small amount of letterpress-printed original writing reflecting on the ideas that drive the development of the papers that each book contains. Each book will call attention to one aspect of the work I have developed in my papermaking practice: color fields, indigo-dyed papers, papers developed in my Ghanaian initiative, one edition dedicated to patterned papers, and the final book focused on highly textured papers. The books will be large in format—18 inches high x 13 inches wide, contain a minimum of 40 pages, and make use of binding strategies that allow the finished book to reference a stack of paper.

From what I have seen, bound together as a book, your deeply colored, patina-dipped, mottled, burnished, layered, and collaged sheets will speak to each other in remarkable ways.

The palette assembled in these volumes takes you to a messy side of life where every color has a past. It’s really satisfying to me, at this late stage of life, to look at a sequence of pages in varying colors and immodestly say, “yes, this is gorgeous,” but that beauty is emanating from material that has been handled, has a history, a relationship to lived experience, is full of subtle imperfection. I spend considerable time in Ghana. There, surfaces in the built environment are layered with historical and cultural complications and tempered by the weather—powerful rainfall and extreme heat. In Ghana, you can look at the color on the surface of a wall, color built up over many years, and you realize you are looking at a historical record—one layer of color is the concrete of a colonial building, then layers of often brilliantly colored paint that have been exposed to repeated torrential rains, eventually painted again maybe with commercial or religious imagery or text, and then again over time refurbished. You look closely at this astounding accumulation, and you see those layers of color and surface reflecting all the joy and pain of life, perhaps the mess of politics, and economics, and layers of cultural activity, and the extreme weather—all of it, taken together, creates this amazingly beautiful surface, with such complex color, reflecting the life of that place. I try to find colored surfaces in the papers that I make that reflect a messy, beautiful complexity. Paper really does have a history that the process and labor of making it builds.