Prior to graduate school, I had not planned on becoming a papermaker. I entered the Design Studies Department at the University of Wisconsin–Madison (UW) with the intention of studying natural dyes and traditional textile processes. But my first semester classes included one led by the great papermaker Mary Hark. We made paper from wild mulberry gathered from a restored prairie outside of town. I was immediately drawn to both the process of gathering and harvesting the plant material and the material possibilities of pulp, water, tension, and time. That first year I made sheets and sheets of cotton, abaca, and flax paper in the well-appointed paper studio at UW, learning something new from every poorly formed sheet until I could finally make passable Western-style paper.

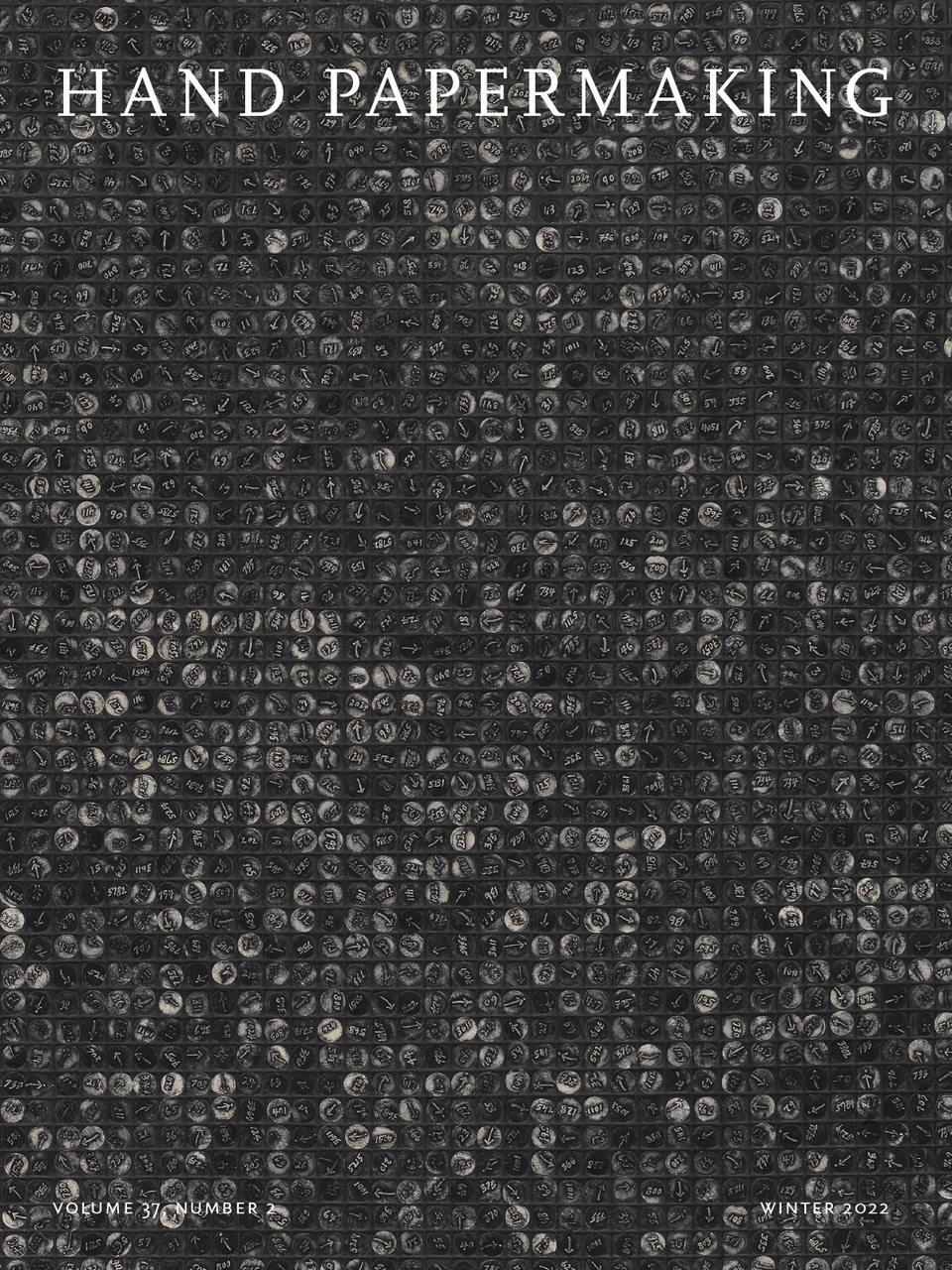

But that was not fully satisfying artistically. I wanted to know as much as I could about what forms paper could take, and what would happen to the pulp when combined with other materials. One day I picked up a tacky lump of overbeaten flax that a classmate had forgotten to throw out. Almost without thinking about it, I formed it into a thick disk and left it to dry on the corner of a table. Over the next couple of days, I observed it shrink and warp as the water evaporated. The final shape was rock-hard and presented me with new expressive possibilities. A body of work themed around geology, fossils, and deep time grew out of this method of working. I made enormous batches of four-hour-beaten bast fiber in the big studio beater, drained it through a layer of muslin, and set out thick layers of this almost claylike pulp to dry on large moulds.

In the summer of 2017, freshly done with an MFA, I had the phenomenal good luck to find a barely used Reina Hollander beater for sale in Springfield, Missouri. My dad and I borrowed my sister’s minivan and drove down from Madison, Wisconsin to get it. Never mind that I had none of the other equipment that you need for a Western-style paper studio, or the studio itself, this beater was absolutely essential for the art practice I was hoping to undertake. I kept it in my parents’ garage. I would have loved to make four-hour pulps with my new beater, but houses in my parents’ neighborhood are close together. Beaters are noisy and it seemed rude to run it for longer than an hour. In addition, I did not have the room in my one-bedroom apartment to set up vats to make sheets of paper. But growing up on a farm in rural Kansas and spending time in the Peace Corps in a remote Ecuadorian village taught me about creative reuse of materials and improvisation. I carry a sense that the world is full of possibility, as long as you are willing to approach a problem from different perspectives, and this has been my guiding principle in my art and papermaking practice.

With my beater stowed in the garage, and the space limitations of my one-bedroom makeshift studio, I began to build a new vocabulary with pulp. I spent the next five years developing a suite of techniques for making paper without a press or a drybox. They are roughly divided into two categories: dipping and pouring.

Dipping Methods

If you do not have a papermaking mould, you can make paper on a string grid, a commonly known technique in papermaking circles. The process is instantly gratifying—wrap string or thread around an empty picture frame in both directions and dip it into pulp to transform it into a solid structure. You can get many interesting effects by varying the thickness of string, type of pulp, and concentration of pulp in the water. Adding just a scoop or two of abaca beaten for one hour to a full vat of water, then dipping a grid made of sewing thread yields a gossamer piece. A vat with a high ratio of cotton pulp to water will result in a chunky, textured piece, especially if you use a thick string like crochet yarn. To dry the piece, allow it to drip over the vat. After it stops dripping, you can prop it against a wall until it dries completely. To remove it from the frame, use a sharp blade to cut around the edge of the piece.

This method works best with pulp that has been beaten for about an hour. Longer than that and the pulp does not accumulate well on the thread, and it tends to contract too much as it dries. Another bonus: this method requires very little pulp. In fact, I only ran the beater in my parents’ garage for one hour per month and had plenty of pulp to continue working.

In the space of about a year of working this way, I developed a number of techniques:

Butterfly Wing Paper: This is paper that is made by building up pulp on a matrix of sewing thread. When the paper is thin and translucent, the thread reminds me of the veins in the wing of a butterfly.

Warp Method: In weaving, one almost always begins by preparing a warp, a system of yarns running in one direction held in tension, which can then be woven with weft material. You can do a similar thing with paper, as long as the warp thread is placed close together. Usually I do this by wrapping sewing thread around a frame with ⅛-inch spacing. When you dip the frame in the pulp, the fibers are long enough to cover many threads at once, making a kind of weft. As the piece dries, small holes develop, which is part of the beauty of the work.

Lace Method: In this method, the order of the threads is controlled by threading them through small holes drilled in the side of the frame. It is possible to make a geometrically regular grid this way, or to create much more complex repetitive shapes. A thin linen yarn is ideal for this, because it is strong and does not stretch much.

Threadless Method: If you use an abaca/cotton pulp with a sewing-thread matrix, you can remove the thread with tweezers. It is painstakingly slow and hard on the hands, but it is like a magic trick to remove the matrix, and the long abaca fibers provide plenty of strength for the paper to hold together.

Bridges Paper: This process is influenced by the aesthetic of visible mending that is currently popular in textile-art circles. It involves days of work to complete and many steps of wrapping thread, dipping in pulp, adding a different kind of string to strategically fill in areas, dipping in a different kind of pulp, and repeating over and over until the whole surface is filled in with complex surfaces. Often I will add bits of fabric or weave into the piece with yarn.

Pouring Methods

In 2020 I finally got a dedicated studio space and moved in my beater. I was able to run the beater at any time for as long as I needed. I branched out beyond cotton and abaca, and one time I accidentally left some kozo pulp in the beater for way too long. Even though I had never been interested in pulp painting, I now had buckets of extremely fine pulp, so I decided to give it a try. I used mineral earth pigments to color it, and embarked on months of experimentation.

At first, I used spoons to apply the pulp paint directly to the screen of a mould, but found that I could not couch it without the whole thing falling apart because the pulp was so fine and thin. I left it to dry on the screen, but it was impossible to remove without ripping. Adding a layer of a longer fiber pulp on top of the pulp paint led to some success, but there were still lots of rips, and I did not like seeing the pattern of the mould surface on the paper.

I tried placing Pellon on top of the mould, applying the pulp paint, and letting it dry, but there was a major problem: fibers of the Pellon became embedded in the paper as it dried and pulled off when I removed the dry sheet. So I would have a gorgeous, earthy sheet of patterned paper, with little synthetic tufts all over it. Next I tried a piece of old cotton bed sheet. That turned out to be the best solution, especially when I spray it with water; it clings evenly to the mould and I can place the deckle over it. There are no pesky fibers embedded in the dried paper, and the sheeting can be used over and over; if it gets worn out, it goes into the beater. I have given away all of my Pellon.

My default backing pulp is 1½-hour-beaten abaca, which is affordable, easy to process, and translucent. I have also used cotton, linen, and kozo successfully. For pulp paint, I find a blend of cotton and abaca, beaten for 5 hours, is ideal, but almost any fiber beaten that long will work. Along with the spoons, I apply the pulp paint with squirt bottles, turkey basters, and pipettes.

To dry the work, you can put the pieces in a press (still on the backing sheet), and then, if you are very gentle, remove them from the backing sheet and dry the pieces in a restraint dryer. You can also let the pieces air dry on the backing sheet and peel them off afterwards. To keep the sheets from getting rumpled and to minimize the texture of the backing sheets (which can make the colors appear muted), you can spritz the paper lightly with water and sandwich it between pieces of absorbent fabric or blotters; I usually use press felts, but other things could work. Place a board on top and leave it for an hour. When you come back, the piece should be nicely flattened, although cockling is to be expected as part of the process. If it has not dried completely, change the fabric and leave it for another hour.

Here are some pouring techniques you can try:

Cloud Paper or Reverse Pulp Painting: While I was in residence at the Morgan Conservatory in June 2021, I made several pieces that referenced rainclouds, because there were a lot of storms while I was there. To make a rain cloud, apply “raindrops” with a colored pulp paint from a squeeze bottle. Allow those dots to dry somewhat, and then carefully apply a gray-pigmented cotton/abaca mix on top of the raindrops, either with a turkey baster or a spoon. Leave that to drain before filling in the whole deckled area with a translucent or white pulp using a turkey baster. Success with this method depends largely on the ratio of water to pulp; you need a good amount of water to get the pulp to spread out and fill the space nicely. It is of course not a requirement that you make a cloud! This is a very flexible method and the possibilities of making art paper are limitless.

Blocking: This is a stenciling process using small objects to block out areas of the surface that will not receive pulp. I use things that I have around my studio like a set of pattern blocks used for learning math in elementary classrooms, old spools, or cookie cutters. Pour watered-down pulp paint around the objects and allow it to dry somewhat before removing the objects. It is possible to make very complex patterns with this method.

Fossil Paper: This is a way of incorporating inclusions into poured paper. You have to be selective about what you are going to embed; it should be fairly thin and porous. Place the object where you want it to be in the sheet, face down. Spritz it with water so that it lies reasonably flat, and carefully pour pulp over it. You have to be accepting of the fact that you cannot completely control where the pulp goes, and that is part of the beauty of the work.

What I love most about working with handmade paper is the way that pulp shows me what to try next. Often I will examine a piece that I at first thought to be a failure, and discover details that are interesting. Then I will try to replicate that detail with intention, and discover something else. This is how most of these techniques came to be part of my artistic vocabulary, and I will likely continue to add to them as long as I work with handmade paper.