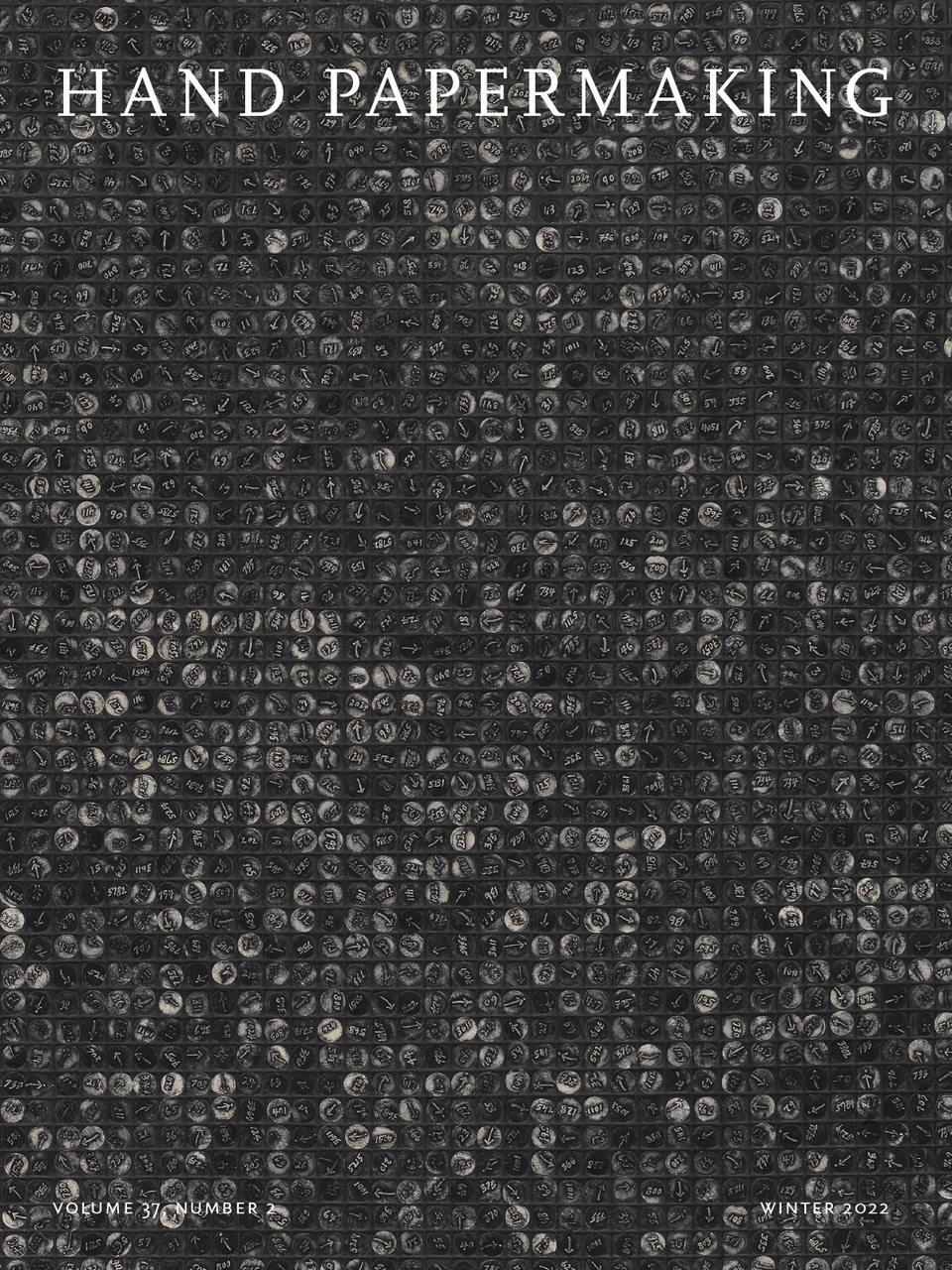

On Thursday, January 11, 2022 I had the pleasure of accompanying editor of Hand Papermaking magazine Mina Takahashi on a visit to Dieu Donné in Brooklyn, New York, to conduct a studio visit and interview with artist, painter, curator, professor, and activist Howardena Pindell. Upon arrival, we were greeted by Dieu Donné Executive Director John Shorb, and Pindell’s main collaborators at Dieu Donné, Amy Jacobs and Tatiana Ginsberg. During the tour of the facility, I was impressed by the multiplicity of Dieu Donné projects featuring artists from all disciplines. Amy and Tatiana set up many tables, covered in brown paper, to show us Pindell’s completed work and works in progress. There were multi-colored oval and square-shaped pieces of handmade paper, covered with arrays of hole-punched dots, numbered, printed, and handwritten with letters, arrows, and ink. My first impression of Pindell's work was that the pieces have profound depth and space, with their overlapping and layered fragments of holes, sealed in by thin, skin-like layers of abaca paper. Like looking into a microscope, my eyes moved around in a circular fashion, inside and through each piece.

Howardena Pindell was born to Howard Douglas Pindell and Mildred Pindell on April 14, 1943 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Pindell’s father was a math and science professor, and her mother was a historian. At an early age her teachers noticed her high intelligence, and encouraged her parents to enroll her in art classes and take her on museum visits. In 1965 Howardena Pindell graduated with a bachelor’s degree in painting from Boston University. Two years later, she received an MFA from Yale University. In 1972 she became a co-founding member of A.I.R. Gallery, the first women-organized cooperative gallery in New York City. Pindell went on to exhibit work all around the world, and built an astonishing career in the art world including, but not limited to, becoming the first Black Woman curator at the Museum of Modern Art.

In the 1970s Howardena Pindell incorporated papermaking in her work themed around construction and deconstruction. Five decades later, Pindell has cycled back to papermaking, immersed in the process during her intensive long-term residency at Dieu Donné. At 79 years of age, she remains a creative force to be reckoned with, and is actively teaching in New York City.

What follows is my interview with Howardena Pindell on January 11, 2022, conducted by telephone. Mina and I were at Dieu Donné in Brooklyn, New York on speakerphone; Howardena Pindell was at her home in New York City.

payton harris-woodard (phw): I wanted to begin by asking if you would talk about color in the work as far as multiculturalism; do the colors have certain meanings to you?

howardena pindell (hp): I learned color theory at Yale when I was a graduate student in the art and architecture program getting my MFA, and I learned a lot about how you can manipulate color in color class, and how they work together, and how you can make one color become somewhat different depending on what you surround it with. Also, I’ve traveled to some extent, and I found different colors have different meanings. For example, red, here I remember you shouldn’t wear a red dress, you know, there’s the red light district. [Chuckles] But in India, red is used for weddings. And white is used for mourning when someone dies, but not at a wedding.

In terms of the strips that I use, I had seen Kente cloth woven in Kumasi, Ghana. And so that’s how the strips came to be used. Cutting them apart and sewing them together. And you never knew, with the color…there would be an interruption because of where the thread was. Anyway, Lowry Sims and I, I don’t know if you know Lowry Sims, who was a Black curator at the Met, traveled around Africa in 1973 and spent about a month and a half there. You know, people dressed well; their fabrics, textiles are really beautiful. MoMA had a show of African textiles and clothing with amulets and body adornments in the 1970s. That show influenced me a lot. It was different from Albers color theory, but it was very different to the point where it kind of got things cooking in my brain. I also, for a show about African art near the UN, wrote an essay for the catalogue about African adornments. That led to my painting Africa (Buddha).

phw: Yes.

hp: Yeah, Buddhism and Hinduism. I practiced Buddhism for a while, and Hinduism for a while. And went back to just being myself. [Chuckles]

phw: Thank you so much Howardena. I was wondering how the domination of the work changed after you received recognition, in terms of feeling dismissed? Or like a token artist?

hp: I was no longer dismissed by a wide group of people. But things were said behind my back, such as one, she was a white member of A.I.R., the first women cooperative and I was one of the founding members and named it, but I was the only person of color. One particular member was constantly saying, while I was not around, that I did not know I was Black.

The most trouble I had was with white women, in or out of the feminist movement. The removal is by omission. And in some cases, there is a domination of white women by other white women, almost like a caste system. I remember when I first confronted and started talking about racism, I was removed from an exhibition. I had brought up Hatshepsut, who was a Pharaoh. When she died, they removed her cartouche from a stone wall-kind of sculpture engravings. Hatshepsut Pharaoh was removed, as artists of color can be removed in other ways, such as when the National Endowment for the Arts invited me to go to the Virgin Islands to be on a sculpture panel for a commission, and I brought one Black male artist, sculptor Mel Edwards for the commission, and a white sculptor’s work. As soon as I mentioned the Black sculptor’s work, the chairman of the committee was very annoyed and said, we will have none of that.

phw: Wow. Thank you. We have looked at some of Mel Edwards’ work here today. That’s great. I love this next question. Where did fragmentation start for you? Where, in the personal or in the work? Did you ever find linearity? I see linearity in the numbers, the lines, and the shapes in your work.

hp: My work changes and backtracks. I am now working on larger spray-dot paintings like the ones I did in the late 60s and early 70s, but they are different. While I work with the spray dots, I also work on pieces that have many attachments that remind me sometimes of the amulets on African textile cloaks. I also work on pieces that have many attachments and a density unlike any of my earlier work. Two pieces that somehow mirror my current work…where I worked with sculpt metal and punched papers that were thick, and I also used heavy thread. That happened, it came and went, and I didn’t continue it, but it seems to be coming back with this new work. I use, now, foam, on canvas, It’s about a half inch, and I coat it heavily with Jade. So it will not deteriorate. I pull on the various strings of my DNA. You were talking about multiculturalism. My complex DNA on my mother’s side goes from Inuit, i.e., Eskimo, to Bosque, from Africa to Portugal, from Sicily to New Delhi and South India. And from Scandinavia to Madagascar and more. I have a very crowded DNA, there is more, but my father is deceased; I am unable to get my full DNA.

[All laugh]

phw: Thank you so much. Yeah, I was reading your book, you talked a little bit about Native American Indian.

hp: Yeah, I also have Greek, Indian, and East Asian DNA. I can’t remember all of it. Nigeria. I think it was Uganda. I have to look at the printout. It was a lot. I thought oh my gosh, Somalia, Sudan, Mozambique, I am going to get myself a calendar-size or poster-size map of Africa, and Europe, maybe North America, because I have Eskimo, or Inuit blood; and just put pins, or some sort of notice to see where everything is, and where the countries are relative to each other.

phw: I think that would be really cool!

hp: Yeah, I think I am going to do that.

phw: I love that. Thank you. We’re gonna move to the next question. So I was thinking back to your time at MoMA, where you were told that abstraction was not considered Black art. What do you think about the term Black art?

hp: I believe Black art was a term designated to work that spoke about issues concerning civil rights and civil-rights heroes. And that abstraction was the route that white artists took, it was kind of white privilege, in a way, because it didn’t mean anything, other than its actual existence. If you look at the Ndebele women in South Africa, I believe they use abstraction when they paint their homes. It’s kind of a geometric abstraction. During the 60s and 70s, non-objective abstract works by African American artists were rejected by the Black community. It has changed, but in the 1960s and 70s, the director of the Studio Museum in Harlem told several of us to go downtown and show with the white boys. I served on a panel with him in Atlanta, about 10 or more years ago. He still was putting me down for being abstract. He didn’t know what I was doing, obviously. Because I have a mixture of issue-related work and abstraction. So, it’s something where there are people within the community who still kind of hold a small, slight grudge against the Black artists that make abstract work. And in the white community, there was an attitude that, why should I buy an abstract work by a Black artist, when I can get it from a white artist and it’s worth more.

phw: Very understandable. Yeah, I agree. I think our next question kind of goes into the same subject. In terms of representation and Black portraiture, speaking to intergenerational Black feminism, generationally speaking, how do you feel the experiences are both shared and different? Is the oppression or dismissiveness of the Black body cyclical?

hp: Sadly, the Black body, including the female body, was used by some Black artists—this is sad—by female and male artists as stereotype images to gain admission into the blue-chip art world. This was around the mid to late 1990s. One artist even had fried chicken served at his opening. The way our country’s going now, I’m furious as to the methods artists of color will use to enter. If the far right wins, there will be no comfort for us in a diverse world under the right wing that seems to be winning. Some artists may swing back to acceptance of negative racial stereotypes to gain entrance, and I find that very depressing. But there are a lot of people of color showing now. I notice recently integrated art magazines have lost their blue-chip advertisers. I noticed this in a recent issue of Art News.

phw: Thank you, Howardena. Yeah, a lot of that in grad school right now. Different world.

hp: Oh, have you noticed that with the magazines?

phw: Yeah. It’s kind of a paradox. And it’s hard as a Black artist to figure that out, you know, you know it but you also want to be noticed…

hp: Yeah, It’s a conundrum, it’s a hard one.

phw: Okay, I’m going to move to the next question. You have incorporated paper in mixed-media work since the 1970s. Can you explain how you worked with paper in the past and how you are working with pulp and paper now?

hp: When I was working at the Modern, I was befriended by the Conservation Department. They were trying to get me into the conservation field. They were really nice to me. I was friendly with the paper conservator Antoinette King. I wanted to make my own paper. She recommended a very high quality water filter. My loft at 322 Seventh Avenue had a darkroom sink and counters. I ruined my blender by macerating Asian papers and embedding dots with numbers written on them while the paper was still wet. Some of them were very cockled. I poured the pulp on a window screen mesh with masking tape along the edge. I dried them between blotters. It was not a very knowledgeable beginning. I am finally doing it right at Dieu Donné. My favorite medium is abaca, which is soooo transparent, it can be very thin. I prefer abaca over cotton, because when you use cotton, the color gets dull but abaca can hold intense color. I love working at Dieu Donné, with Amy and Tatiana, because I can use my favorite techniques, including layering. I love layering, you may have noticed that in some of the pieces.

phw: Yeah. At Dieu Donné, me and Mina were looking at the colors you’ve used, and the abaca on top, like that thin layer. So nice. Really, really great.

hp: I love the back also.

mina takahashi (mt): If I could jump in here...when you’re talking about layering, there were a couple of pieces where I could see that you’d laid in the dots and then maybe they put a skin down and then you laid in more dots, and it just gets so complex. And I feel like it’s a bit like an equation somehow.

hp: That’s interesting because my best subjects, one of them was chemistry and I loved balancing chemical equations. My father was a math science person teaching in the 1930s, he was principal of a school, and actually, was an activist. They were trying to get the school system, I think it was Annapolis Maryland, to pay black teachers the same they paid white teachers. Black teachers were making the same money as white janitors. My father was a principal of the school, and then he started an African American union within the school. He became a common pleas court administrator in Philadelphia, where he remained until he passed away at the age of 98. He was very strong, he grew up under segregation where kids had to walk like five miles to school every day. I had a good education at home. And I went to good schools, and my mother was a historian and third-grade teacher. One of the first gifts that I was given was a microscope as a child.

mt: Oh, that’s interesting.

hp: So I was looking at drinking water in Philadelphia and it was very busy, things were floating around in it, swimming around in it.

[All laugh]

phw: Okay Howardena, we’re gonna move to the next question. How does papermaking differentiate from painting and other disciplines in your practice? Or does it? Now that you are in a sustained engagement with papermaking at Dieu Donné, do you find that the process is informing other areas of your current practice?

hp: It is encouraging my use of layering. But with painting, I attach non-archival materials that are covered with Jade. They are sealed in, so they don’t fall apart. That creates a highly textured painting surface. The large grid piece I am working on now, the large one that’s over at Dieu Donné, has a kind of a density, because there’s more density of cotton pulp…they probably showed you the grid I’m working on.

mt: Right. The little squares that will then get joined?

hp: Yeah, I have a bunch of them here to work on at home. There is more density to cotton pulp than there is to abaca. I find the delicacy of paper…my painting is much denser. I also like the way I focus. When I work at Dieu Donné, I focus. Amy commented on that. I just focus right in, which is different from my painting because I come and go, and come and go, just because I have things I have to do. And I do have assistants, but poor souls, they’re punching holes, or dots. I like the way I focus as I work on paper. My work generally is large in painting. Working with the paper pieces—it’s just dawned on me—I see the whole work completely. And the work is within arm’s length, no matter where I reach. But, painting is the opposite, because it’s so large, you get kind of engulfed by the painting. But, I like the fact that I can see the whole piece as I’m working on it, rather than a section, section by section. I can focus on making it in one intense period of concentrated energy. The large grid piece using cotton I will work on in sections. Small enough for me to take home and to my studio in the Bronx. I love working at Dieu Donné, and I really love working with Amy J. She’s wonderful.

mt: She is!

phw: Thank you so much, Howardena. One final question we wanted to ask you. You spoke about your father being a mathematician.

hp: Yes.

phw: We were wondering what is the significance of the numbers?

hp: Oh, I call them nonsense numbering. When I first started out using numbering, I did everything sequentially, and not anymore.

phw: Okay!

hp: It’s just all intuition. Numbers and arrows. I was also working with television and photography, using acetate and writing numbers and arrows on the acetate, and sticking it to the TV screen and then photographing it. My father was always writing numbers in a book. He was recording the distance he had driven. So he always had a gridded notebook that he was writing numbers in. And that kind of fascinated me. But, you know, I had no idea what the numbers were, or what the logic was.

phw: Okay. Well, thank you so much Howardena.

hp: Oh, you’re welcome.

mt: Howardena, if I could? I just wanted to make one comment because I keep hearing it over and over again in my head, when you said that the first gift that you had received was a microscope—

hp: Oh yeah, I have a new one. I just bought a new one.

mt: —and then you were talking about Dieu Donné being a place and a space to focus. And it really made me think of Dieu Donné as a microscope for you. And the way you can focus in on those squares, as if they are like little glass slides that you would view in a microscope. I can see the dots being alive and moving, having a kind of kinetic energy to them.

hp: That’s interesting. I think that’s especially true of the layered ones.

phw: I think I see them as celestial bodies. Very interesting.

hp: Yeah, I know one thing I’d like to do more of is the dots that have little dots punched out of them, like in that brown one.

In a follow-up email exchange, I asked Pindell about her overall impressions on returning to papermaking after nearly fifty years. She replied, “Finally, now I know what I am doing. My early attempts at papermaking were rudimentary.” Nearly 80 years of age, Howardena Pindell has extended her time in residency at Dieu Donné, where she is currently excited about working with papyrus dots layered on top of an abaca base.

Editor’s note: To coincide with the exhibition “Howardena Pindell” at Garth Greenan Gallery, New York, September 15–October 29, 2022, Dieu Donné and Garth Greenan Gallery have co-published Howardena Pindell: Numbers/Pathways/Grids, a catalogue

featuring the new paper pieces created in residency at Dieu

Donné. 126 pages, 10½ x 8 x ½ inches, texts by Gilles Heno-Coe and Re'al Christian, and full-color illustrations throughout. For more information, contact Garth Greenan Gallery, www.garthgreenan.com or Dieu Donné, www.dieudonne.org.