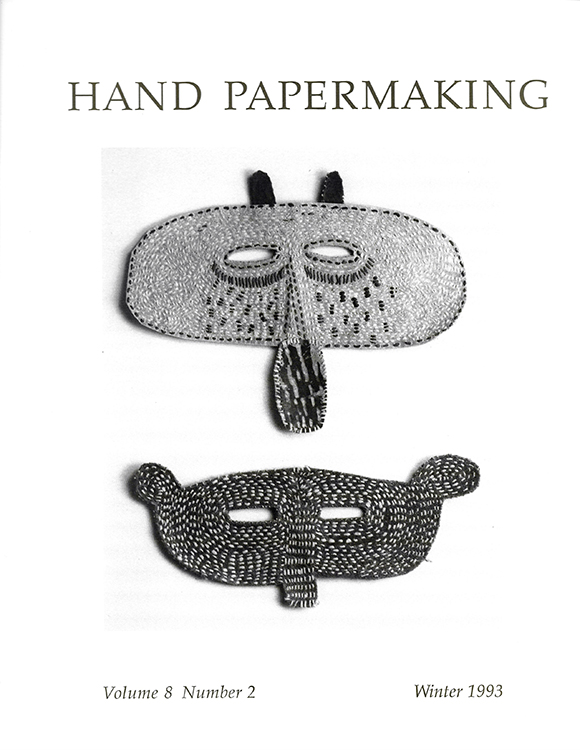

Marilyn Sward: I think it is interesting to establish where you fit on what I always think of as the Paper Tree that is rooted in Douglass Howell and contains several early branches. Mary Ann McKellar Schwarcz: I was at the University of Iowa studying printmaking. After spending a year in British Columbia, I came back to take the paper course with Tim Barrett. Sward: So we will put you on the Tim Barrett branch. Is that where you began to use flax? McKellar Schwarcz: Yes. I was introduced to the different fibers in class and I wanted to see what they could do as far as strength and manipulation. I directed my attention to flax because of its natural color range; you didn't start out with a stark white sheet. I remember the abaca as being too mimsey for me. When I first started using flax I wasn't gelatin sizing it and I wasn't using beeswax. I was doing more with making sure the sheet was really worn before I started. I was puncturing holes in it, as well as creasing and burnishing it. So it really didn't look like a sheet of paper at all. Sward: Did the stitching start as a construction technique and then evolve to patterning? McKellar Schwarcz: The first stitching was on a rain stick, based on those of South America. I had taken a branch and split and hollowed out the center to create a channel. Gravel and stones were encapsulated in this channel, allowing a tumbling or "rain" effect when the stick was tipped from end to end. The whole piece was covered with flax paper, drawn taut by stitching with kozo thread. It wasn't very effective as a rain stick--it didn't have that continuous little sound--but it was a nice imitation. That led to other forms. I liked the durability of the form and the stitching. I could really stretch it around and make it work. Sward: It occurs to me that we are speaking of craft and technique, your forms and methods are highly unique. How do you feel about the sharing of process? McKellar Schwarcz: Well, I think that addresses the issue of working by yourself versus working in a group. If you start from one point and give people the information that you have researched, then they can go on from there and you have furthered the craft. That seems important. Why make everyone go back to the beginning to learn and make the same mistakes? That's what the good teachers like Tim Barrett do; they give you all the information they have and you can go on to develop it. Working in a group it happens faster. It's an issue of being isolated out in your own studio, just doing your own work, versus having a community of papermakers that come together and share ideas frequently. Sward: You are saying that by coming together and sharing ideas you are furthering... May Ann: An exchange, yes. It's much quicker. Sward: You are building information faster. McKellar Schwarcz: Yes, and that's what I realized when I was up in British Columbia. There was isolation in having no one else around who did anything art-wise, not wood cuts, printmaking, or papermaking; nothing. And then coming back to a group of other artists and talking about your work... I'm not saying that you have to work side-by-side the whole time, but I think there is a need for the community and the sharing of techniques and ideas. Sward: I think we all also have a need to get away from too much work and too much art community. McKellar Schwarcz: You do need that time to do your own work. I always need to go through a period of boredom and I don't really start creating until after I've gone through that. It drives you crazy while you're doing it, because you feel like you're wasting time. You're pulling at different things and you're not doing new work or it's not exciting. I always have to go through that, no matter what. Sward: Do you care if people know your work is paper? McKellar Schwarcz: No, it really doesn't matter to me what material something is made out of. I think so many people making paper now are still dealing with the process and the newness of the material, or their experiences with it. They stop too soon, as soon as the sheet is prepared. And they're so excited about what they've found upon the dried sheet that they don't take it from there. They see it still as a sheet and don't incorporate it into some other form. As a result, we see the same boring forms over and over again: kite shapes and cylindrical structures with nothing really done to them. I think of an image, then I think of material that's easy for me to use, to achieve the image I want. If it takes putting a wood cut on top of a piece of paper or doing an etching, or incorporating any other skill that I have, then I'll use it. Sward: The images in many of your forms remind me of masks of British Columbia, the ones done in Amate, the Maori, and African decorative techniques. What are your sources? McKellar Schwarcz: Well, I have both African and Northwest Coastal inspirations. I think the African influence comes from being at Iowa University, seeing the Stanley Collection there, and attending some of the conferences that were held on African art. Sometimes the inspiration is reading about masks and the other objects, what they signified or how they were used. The idea is stimulating enough for me to create my own image, how I would feel about that subject matter. Other times, the form itself intrigues me, like the plank masks and the fact that a person can wear a circular mask and be able to balance the plank continuing on up, the extension of that form on top of the human body. Or some of the other Cameroonian masks and costumes that I've seen. But I don't want to copy them; that's not my idea. Sward: Was it a coming together of the Stanley Collection and the skill of papermaking that you were doing with Tim that brought those two elements together in your work? McKellar Schwarcz: Well, I think before that it was my living up in British Columbia. It was seeing the African work and then living up there and becoming more familiar with the Northwest Coastal work. Sward: I know you talk a lot about Eskimos, too; their techniques and what they do. McKellar Schwarcz: I've seen the life style of the people who are working there now, especially the isolation of the individuals from what's going on with the rest of the world, and how that really doesn't matter in their creation of a piece of work. Because it really is between you and whatever you're using to express yourself, whether it's through making visual art, music, dance, or whatever. Having that experience, living there myself and seeing how other people used art, that was much more useful. It was direct in a much more honest way than what I saw when I came back down here: people going to art school and knowing they wanted to make art but not really having anything to say; not having the life experiences or the lifestyle that would lend them to making work. Sward: I see that in your work, in the kinds of processes that you do. They seem to bring it closer to you in a family or a life context; that you run the spindle as you watch TV and that your daughters help you with some of the steps. That all feels to me very much like what you're describing with the people in British Columbia. What about all of the animal images? McKellar Schwarcz: Well, I like animals, a lot of times much more than people. I think that people don't put enough weight into what animals can contribute just in their being and to living in conjunction with animals and the whole environment. Consider how earlier people relied on animals in order to make it. Now most people just treat animals as a sort of commodity. They put them in zoos, or they treat their pets like objects that they take care of, instead of really trying to understand them. I find animals to be so expressive, wild and domesticated both. Sward: What do you think of the idea of a mask as something a human puts on to become an animal? McKellar Schwarcz: I think a lot of people's personalities match animals. I don't think there's that much distance between people and animals. Sward: The dog owner that looks like the dog? McKellar Schwarcz: Oh, yes. But any animal, not just dogs --although I like dogs and would have a million of them if I could, except it wouldn't be fair to the dogs--whether it's a bird or a fish, no matter what people say about the size of their brains compared to man, each still communicates with people. I'm interested in how people have lived with animals in the past and have believed in the spiritual being of those animals. Sward: Do you think about the shape of the animal too? I am struck that you chose to use the platypus, for example, and by the humor of the shape of the animal. McKellar Schwarcz: Oh, yes. I also think of the brilliance and the patterning of colors, like with salt water fish. Some of the animals that you don't see as much any more, that are extinct or rare, their structures are incredible. Sward: Now I have to ask, was the Bill Anthony piece an animal portrait of Bill? McKellar Schwarcz: No. When you lose friends that are close to you, you feel, even though you haven't known them a long time, as if there's something that ties you to them. Although I don't consider myself a religious or spiritual person, per se, I sense that some of these people's spirits do come back to you. They are overseeing what you're doing as you're working and as you continue to live. In our society you bury a person, you put them in a grave or cremate them. In some of the other cultures now and in the past they did something that creates a visual memory of the person that stays with you. Sward: That you keep? McKellar Schwarcz: Yes. I wanted to think of a piece that I could do in memory of Bill, as well as an intermediary between the individual in this world and the supernatural. The sculptural form was based on the African plank-style memorial effigy, displayed by being set into the ground or leaned up against the side of a house. The elaborate stitching creating a rich textural surface on the piece was a commemoration of Bill's mastery as a craftsman. Sward: Your "tools" are flax and kozo. Does the fiber relate to the animal form for you and/or to antiquity as a reference through color and texture? McKellar Schwarcz: I think the natural color fibers relate much more to animal colors. I haven't found how to use the brilliant colors to be satisfied with the end result, or I would choose to put more color into some of my images. It's something that I want to do. Sward: You were mentioning the tropical fish patterns. McKellar Schwarcz: Yes, and some of the birds and the subtle, different variations in some of the animals. But I haven't been satisfied yet with what I've been able to accomplish without looking too slick or too commercial, or just too boring. Sward: Too exact, maybe. I find a sense of whimsy and a sense of humor in your work, and somehow brilliant color doesn't seem to be something that contributes to that. McKellar Schwarcz: I haven't used it as one of the elements to bring out what I want in the form. And I think what I try to get most is the feeling of the animal that I'm trying to bring across, the expression. That's why sometimes the mask will change from what I start out with. For example, I've been doing some reading on coyotes and the trickster character associated with them. I'll start making a coyote mask and then, as I'm working on it, it develops a different personality. Why try and change it to make it into a coyote when it may lead to another animal that may be more appropriate? It may not end up being a coyote. It started with the coyote spirit and became something else. Sward: I feel that your images are very powerful. Recording our conversation like this is simply embellishment and background, an introduction to who you are and how your thinking parallels the work. I think the work is strong and stands for itself. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Sward: I find a sense of humor and playfulness in your work that reflects upon children and "outside" art. I wonder how you feel about students making art. McKellar Schwarcz: I think they should be making art for themselves, not for anyone else. As a child you start making art or use art as an expression for yourself, but as you go along, and especially if you go through art school or some formal education, how much of that is for yourself and your development, and how much of it is for someone else? And there is the influence of the business aspect of art and what sells and what doesn't sell; how that makes you choose depending on how strong your feelings are and your financial situation. Another issue is how much you compromise yourself or why you make your art. Why you are an artist and the person next to you--who probably started the same way my children are starting now, to use art as some sort of personal expression--why are they no longer using that personal expression in that way? Why does our society cut out for most people that element of self-expression, which many of these primitive cultures that we've talked about do not? Sward: So you feel that the attraction we have for "outsider" art is the base that it has in reality? McKellar Schwarcz: Part of it touches on the element of time again; the availability of time and the period of time that you have to go through, the boredom. In dealing with children, I think about how adults think they have to be busy every moment. They go from this activity to that one. They have to be developed for this one, they'll be behind if they don't take this class. They never have a chance to have a time to direct their energies to something they want. They may not know what they want at first, but if you have the television set there, video games, or something else that they can so easily cop out with, then they're not putting anything out. So they never have a chance to develop their own interests or fulfill their needs that way. Sward: As we move that technology closer and closer to children, we probably stifle that hands-on creativity even sooner. Here we are back to children and families and life; I feel that again reflects the integration of your work to meaning and purpose. McKellar Schwarcz: That's part of the whole idea of acceptance. Artists are expected to be professional; you are professional or you are nothing. Nobody talks about their children. They ignore the whole issue. Sward: I always hope we have moved beyond that. Margaret Mead said that to be cultured we must give credence to our young and old. I think this conversation points to the importance of your feelings for your family and I hope that will make other people realize they can discuss art and life in the same breath.