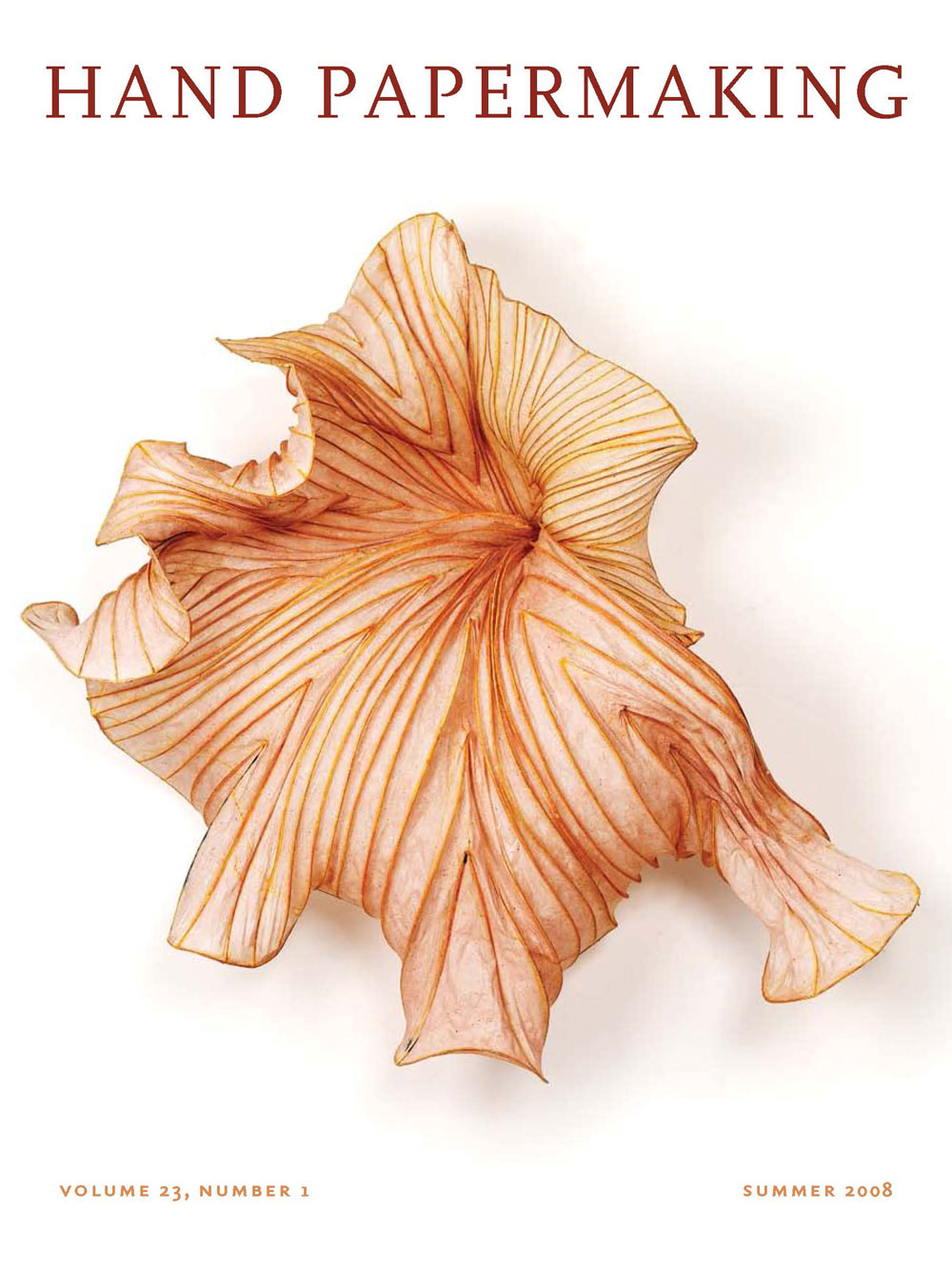

Gentenaar set up his first papermaking studio in the 1970s, at a time when papermaking was not yet recognized as the art form that it is today. There was no network of other artists working in handmade paper as a medium. He had been making embossed relief prints—by printing images on sheets of Plexiglas into which he scratched and drilled grooves—but as he tried to make deeper grooves in the material, he found that the commercial paper he was using could not conform to the surface of the Plexiglas without tearing. So he decided to look into using fresh sheets of wet paper. Gentenaar received two grants from the Ministry of Culture in the Netherlands, which allowed him to work with Joop Persoon, the head of the fiber laboratory at the Royal Dutch Paper Factory in Maastricht. Persoon taught Gentenaar the basics of industrial papermaking and supplied him with materials to work on his own. Inspired by the equipment in the factory's laboratory, Gentenaar did not form sheets in a traditional way, but built a sheet former—a deckle box that used a vacuum pump to suck the water out of the wet paper pulp. Over several years, he developed better vacuum equipment using systems adapted from other industries. He combined methods that are used to extract excess water from freshly poured concrete and water-separating technology from cow milking machines. His vacuum table is a flat, screen-wrapped surface which is covered with thin plastic foil during the vacuum pumping process. ON Peter Gentenaar: Paper Innovator helen hiebert Peter Gentenaar, in the Hollander shed, Summer 2006. Photo: Piet Gispen. All photos courtesy of the artist. Barokke Bestrating \[Baroque Paving\], 2006, 120 x 100 x 30 cm \[47 ¼ x 39 ½ x 11 ½ inches\], bleached flax pulp poured on a bamboo frame. Photo: Piet Gispen. With a strong pump, Gentenaar's vacuum table evenly spreads the pressure under any surface. This system allows him to work very large, since he pours sheets rather than pulling them from a vat. Eventually, Gentenaar built a vacuum table large enough to make a 2.5 x 2.5 meter sheet of paper. Later, for a public commission, he doubled his table surface to 2.5 x 5 meters in order to produce two sculptures which he had cast in bronze. These forms now adorn a bridge in Rotterdam. Since 1973, Gentenaar has worked primarily with overbeaten, bleached Belgian flax, a fiber that is normally sold to linen spinning mills. He started out using a Voight Umpherston Hollander beater, which he put to the test with the long-fibered Belgian flax. The fiber often clogged the beater and occasionally caused blackouts on his entire block. After repairing the Voight many times, he became familiar with the mechanics and designed his own beater, the Peter Beater. His beater has the same type of roll as the Voight, but is fabricated with a horizontal, instead of a vertical, pulp flow. The design alteration makes it better suited for long fibers. He has produced over eighty Peter Beaters which are in studios around the world today. Gentenaar became intrigued with paper pulp's shrinkage properties when he accidentally dropped a match into a wet sheet of paper and saw the tension created between the match and the paper as the sheet dried. He began making sculptures by constructing flat armatures out of bamboo strips. They resemble giant spider webs. It is a technique he still utilizes today. He lays the armature on the large vacuum table and pours the pulp over it so that it surrounds the bamboo. He engages the vacuum which sucks out 75 percent of the water. With the help of ropes, pipes, pulleys, and clothespins, he carefully elevates the two-dimensional sheet (with the embedded bamboo armature) from the vacuum table surface and shapes it into a three-dimensional form. He dries the sculptures as fast as possible with the aid of dehumidifiers, a huge fan, and heat. Gentenaar has found that fast drying makes the pulp and bamboo forms twist into dramatic spirals. Gentenaar notes that no matter how detailed and fragmented his bamboo design is, the pulp dries in a way so that the armature and the pulp unite into one movement, where every aspect of the form influences the overall sculpture. Basic shapes and forms react differently to shrinkage during the drying process: a triangle will remain rigid while a rectangle will twist itself into a butterfly. These forces of nature—set against the memory of the plant fibers which are always returning to their spiral forms— give his sculptures their rich and baroque shapes. Gentenaar finds satisfaction in trying to imagine how a two-dimensional armature will look after it dries into a three-dimensional form. He happily accepts the surprises of nature as part of the process. The vitality of the material keeps Gentenaar inspired. His forms come to life as they are lifted into space, twisting and writhing as the pulp bends the bamboo into its final sculptural form. With ingenuity and determination, Gentenaar creates large and dramatic sculptures from a material that we usually regard as soft and delicate. And if he does not like the results of a certain piece, or if gravity pulls down the wet and heavy pulp off from the armature, he just does it again—an awesome feat at this scale.