We live in an age of expansive interpretations, in a timewhere much of art is moving from static to mobile interfaces. Yet art gives usthe opportunity to experience what we cannot see—for example, there is stillthat material moment for many of us, when we put our hands into a papermakingvat, feel the moving water, and recognize the familiarity of the actions whenwe engage with pulp. Those of us who have come to hand papermaking fromprintmaking appreciate the poetics of retrieval. Taking impressions, we makeprints. It is a heightened activity that provides new syntax and increasedassociations. In discussing his concept of “liquid modernity,” the great Polishphilosopher Gustav Bauman comments on how we have moved away from a “heavy” and“solid” hardware-focused modernity to a “light” and “liquid” software-basedmodernity.1 However, technologies can streamline but also disembody. “By nowmost of us have figured out that machines don’t save time and work, they justsubstitute another kind of work and often require more time,” says book artistand media personality Pattie Belle Hastings.2 In hand papermaking, theconsuming process of preparing the material and working the pulp gives us timefor conceptual and creative thinking which leads to the expression of rich,complex ideas in the work. Through the hand papermaking process, we findmulti-media possibilities for layers of meaning with hidden ingredients and acapacity for mimicry. Papermaking offers hybrids of different technologies suchas surface articulation for photo and digital photography, the ability to makelightweight components to challenge spatial expectations, ways to invitenatural reactive interventions by introducing material into the pulp, and toexplore paper’s relationship to its environment by means of translucency andstrength. The artist can investigate paper’s distinguishing characteristics ofexpansion, contraction, and rebuilding through burning, scoring, and cutting.But most interestingly, handmade paper allows a certain level of concentrationand focus in the fluid electronic age. “Paper comes from the reorganization ofa destroyed past,” explains Sandy Kinnee.3 In his work The Mummy’s Curse andthe Armani Suit, Kinnee explores the allure of mummy paper. As the demand forpaper rose in the 1800s, the price of rags soared. A previously untapped sourceof cheap rags was discovered by the owner of a papermill: Egyptian mummies. Heimported a boatload of them and removed the linen wrappings, which were thenconverted to pulp. While turning the pulp into butcher paper, the mill workerscontracted cholera. The story, while fascinating, is no more than a tall tale,concocted by the mill owner himself. Yet something about mummy paper catchesour attention: it is the idea that a sheet of paper can be more than it appearsto be, in this case, the engine of an ancient curse. Paper has the potential toembody elements beyond dimension, color, and texture. It has a history. Theruined or discarded is reshaped into a new form, reincarnated, and given newlife. On the way to becoming paper, a bale of cotton waste, the pages of a200-year-old book torn loose from their binding, or an Armani linen suit thatno longer fits is reduced to a bucket of worthless, tangled, threads. The soggymass retains a history of having once been an Armani suit and maybe the memoryof how good someone looked in it. Symbolically, paper is an answer to the humandesire to start anew. “For me,” Kinnee states, “the unseen attributes withinthe strands provide an excuse to make pulp…Making paper is far toolabor-intensive to be undertaken without proper justification. I find my excusein the provenance of the material. The invisible and poetic dimension ofpapermaking is the bond it makes between the past and the creative act in thefuture.” For Eve Ingalls, hand papermaking offers “a medium that creates adynamic bridge between nature and culture.”4 Paper is a natural product and asurface on which we document crucial aspects of society. In her work Empire onCourse, Ingalls uses offwhite paper to signal the presence of a writing/drawingsurface on which thinking and mapping have taken place. And yet the paper isnot flat. She encourages pulp and water to react to natural forces and becomeactive participants in the building of form. She creates flexible armatures byplacing wire between newly formed sheets of paper that become twisted by theshrinking action of the drying process. The action is similar to the spiralingof a dead tree trunk as its drying cells collapse. The thinner wires allow theforce of the drying paper to dominate, resulting in a pastoral environment ofrolling hills. The thicker wires restrain the freedom of the paper, just as urbandevelopment restrains nature. This results in a flat, rigid terrain of citygrids. In another paper sculpture Fingering Instability, Ingalls lets thenatural flow of water act as a drawing tool. This process suggests thefragility and breakdown of human attempts at survival in the face of nature’spower. Layers of meaning accrue from the reactive interactions between culturaland natural references in the sculpture. Ingalls enjoys handmade paper’s greatexpressive potential. “It can express the lightest of air molecules and theheaviest of stones. It can be as smooth as glass and as rough as tree bark.Paper can feel erased, burnt, or gnawed away, and it can therefore suggest thatboth cultural and natural elements are struggling to survive the effects of environmentaldegradation. Paper is an ideal medium in which to document the intricateeffects of wear and tear on the natural as well as cultural fabric of theearth.” Ingalls also appreciates papermaking’s capacity to forge a link betweenancient processes and current technological developments. “In Thailand Ilearned ancient techniques of papermaking…But I also engage in techniques inpapermaking that have been inspired by new technologies. In many of mysculptures I have used visual ideas developed in Photoshop and similarprograms.” For It’s Only a Wave, Ma’am, Ingalls created a model, scanned it,and gave the scan to an architect who translated it into a set of drawings. Thedrawings were in turn given to a fabricator, who constructed a stainless-steelarmature that she covered with handmade paper. “The play of the two worlds, thenatural and the technological, added a great deal to the meaning of the piece,which is about climate change,” Ingalls describes. “Papermaking, a superblyrich and expressive medium, places me in the ‘thick of things,’ where the pulseof life can be felt with exceptional intensity.” Rie Hachiyanagi explores thecultural significance of a sheet of paper in her work Silence. “Paper wasoriginally invented to record and transport human expression across time anddistance,” states Hachiyanagi. “Paper is intended to have a voice attached toit, thus without markings it remains silent. Yet, a blank piece of handmadepaper with its unique qualities can express what words cannot.” ForHachiyanagi, the origin of paper parallels that of humanity. “Although plantfiber grows naturally, paper cannot come into existence without human hands…Wecannot give birth to ourselves yet we must recreate the self. I believe thatboth the existence of paper and the way we exist are verified only throughexpression.”5 Recently Lisa Hill worked at Pyramid Atlantic with Director ofthe Papermill Gretchen Schermerhorn to create a massive body of work stimulatedby the similarities of paper and skin, exploiting aspects of science andbiology. Hill created a group of books, encasements, and large-scale, suspendedworks that examine various membrane structures and explore flax paper’sinherent ability to hold its strength while being manipulated by removal, puncturing,shrinkage, and stretching. In her project, paper is a personal mapping device,revealing scars and disfigurements that tell its story. “Just as skin does, thepaper I create communicates visually and tactilely through an unspoken languagethat is layered and complex,” explains Hill. “Some of my work is so fragilethat you might wonder what holds it together, what secrets it held and whatvulnerabilities it keeps at bay… Much like folds of skin, I reveal and hideinformation by layering hundreds of sheets of paper that curl away from eachother, come together, curl away again, and come together again. The interiorand exterior implications of this are palpable and the effect creates a certainlevel of intimacy, which is deepened by the haunting shadows of the dark gapsin between the ‘pages.’”6 In a cross-disciplinary investigation, Hillapproached papermaking with conceptual ideas formed between art and science, aninterest in digital media, various resources, and samples. As her technicalpapermaking assistant, Schermerhorn was the responsive and skilled hand toguide Hill’s creative expression in the papermaking studio. Schermerhornintroduced various pulps that best suited Hill’s project and created anenvironment for Hill to experience the medium and develop her own personaltechniques such as using a spatula to remove extremely thin sheets from themould. For Hill, indeed the paper–skin connection has personal resonance. “Skincells may be the key to stem-cell scientific development that will result incures to diseases and conditions like Lupus,” asserts Hill. “My daughter wasfirst diagnosed with the disease because of a butterfly skin rash. Working withpaper that has a history and timeline mirrors skin which contains informationabout genetics and identity. It is skin that protects us, envelops us, andthrough stem-cell applications, could very well be the source of a body’s‘healing.’” Finally regarding my own creative work, I believe that the newmedia alternatives have their ancestry in the white of paper and the essence ofcelluloid; therefore I use the essential information carriers—paper andelectronic media—as my expressive materials. Through the transformativequalities of these materials, I am interested in investigating where the visibleand invisible lay side by side. My multi-dimensional pieceSuspension/Scieran/Shorn (2001) reflects on a person experiencing two states ofbeing, a landmark between two things, an island in the midst of the sea, acivilization transforming itself, and new technology that is always alteringour way of thinking. The work identifies the dual sense of self in thetwenty-first century. I enjoy investigating the story as it emerges and becomesvisible either as material substance or electronic imaging. Language is animportant part of the work to create inner sound and movement so I often workwith artist books as a component of a larger installation work that, in thiscase, includes cast paper, watermarks, video projection, and sound.Suspension/Scieran/Shorn is a play of opposing traditions, that of materialshand formed and that of resources electronically conceived and produced. In amore recent work titled Release, How Can We Go Forward When We Do Not KnowWhich Way We Are Going? (2007), I again explore the intersection of old and newby utilizing digital technology to capture iconic, memory-laden images and burnthem onto handmade paper, returning to a Japanese tradition of smoking paper.7In summary, many contemporary artists are choosing handformed paper for itsstriking translucency, strength, nuance, and rich expressiveness in theirprinted or sculptural works. They experience a certain level of concentrationin our electronic age in the physicality of the material. And their works showthat visual artists have clearly discovered paper as a solution for new visuallanguages and renewal. ___________ notes 1. Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity(Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2000). 2. Pattie Belle Hastings quoted inexhibition brochure accompanying “Raptured Browsers: Books as Visual Language:Pattie Belle Hastings, Clifton Meador, and Ward Tietz,” at Pyramid Atlantic,October 31–November 30, 2006. 3. Sandy Kinnee, working abstract prepared infall of 2006 for “Why Beat Pulp?” CAA panel, February 15, 2007. Sectionpertaining to Kinnee is quoted and adapted from his working abstract. 4. EveIngalls, working abstract prepared in fall of 2006 for “Why Beat Pulp?” CAApanel, February 15, 2007. Section pertaining to Ingalls is quoted and adaptedfrom her working abstract. 5. Rie Hachiyanagi, working abstract prepared infall of 2006 for “Why Beat Pulp?” CAA panel, February 15, 2007. Sectionpertaining to Hachiyanagi is quoted and adapted from her working abstract. 6.Lisa Hill, e-mail message to the author, December 20, 2007. 7. Release wasincluded in the exhibition “Of Paper” at the Montpelier Cultural Arts Center,Laurel, MD, September 7–October 26, 2007. The show featured eighteen prominentregional artists working in hand-formed paper. Catalogue available, contactRuth Schilling Harwood at the Arts Center, tel 301-953-1993.

Sandy Kinnee, What You Can See Won’t Hurt You, Will &Won’t Armani Suit B, 2007, 30 x 22 inches, various marks on handmade rag paper.Photo: Charles Walters. Courtesy of Art Selection, Zürich.

Eve Ingalls, It’s Only a Wave, Ma’am, 2006, 9 x 12 x 13feet, stainless steel, abaca handmade paper. Photo: Ricardo Barros. Courtesy ofthe artist.

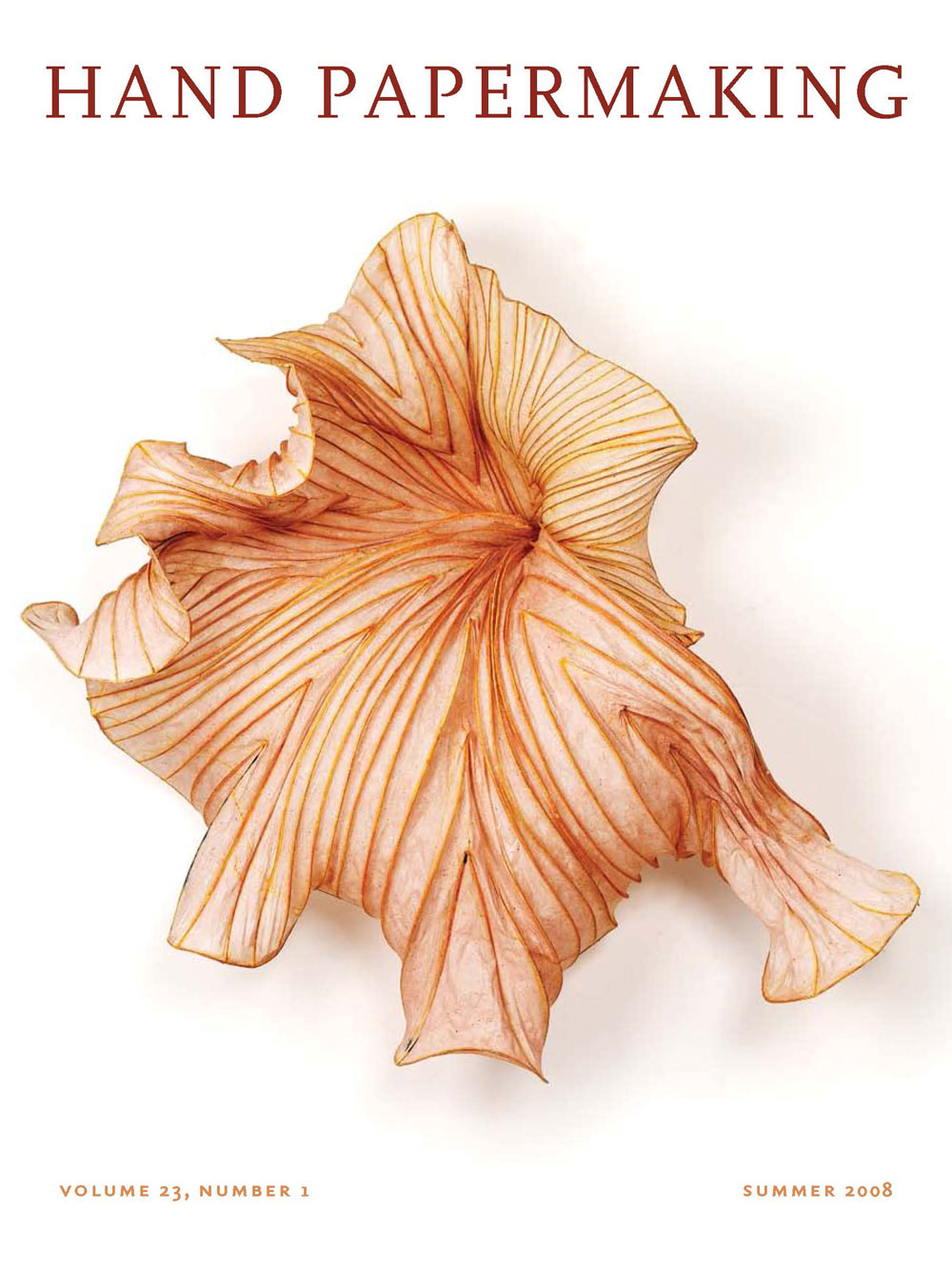

Rie Hachiyanagi, Silence, 1999, 14 x 14 x 12 feet, Japanesekozo paper, installed at the University of Northern Iowa Gallery of Art.Courtesy of the artist.

Lisa Hill, detail of Tegument: Time, 2007, 70 x 11 inches,pigmented raw flax, wax. Assisted by Gretchen Schermerhorn at Pyramid Atlantic,Silver Spring, Maryland. Photo: Greg Staley. Courtesy of the artist.

Helen Frederick, Release, How Can We Go Forward When We DoNot Know Which Way We Are Going? 2007, installation: artist-made flax paper (20inches in diameter each), smoked with solar plate etching and chine collé, andfound objects on wall-mounted shelf. Courtesy of the artist. Helen Frederick,detail of Scieran, Shorn, Shore, 2002, 16 x 6 inches, watermarks in artist-madeflax papers. Courtesy of the artist.